Candles or Costumes? How Late-October Traditions Diverge in the U.S. and Germany

In my last post, I reflected on Erntedank—Germany’s church-centered harvest thanksgiving—and contrasted it with the United States’ family-and-food-focused Thanksgiving. This time, I’m staying with the season but shifting a few weeks forward, to the point where autumn deepens and cultures turn toward memory, identity, and—depending on where you live—either candles and quiet or costumes and candy.

Around October 31–November 2, the calendar stacks several observances: Halloween (October 31), Reformation Day (October 31, in Protestant regions), All Saints’ Day (November 1, in Catholic regions), and All Souls’ Day (November 2). They sit side-by-side on the calendar yet serve very different purposes—fun and folklore, reform and identity, remembrance and prayer. And that’s what I’ll reflect on in this post.

Halloween in the United States: Roots and Reinvention

This time, let’s start with what led me to write this post: Halloween.

Long before “Halloween,” Celtic communities in Ireland and Scotland marked Samhain (literally “summer’s end” and pronounced “sow-win”) at the turn from harvest to winter. It began at nightfall on October 31 and continued into November 1. Ancient sources and later scholarship describe it as a time when the boundary between worlds was porous; communal bonfires, protective rites, and disguises served to manage perceived spiritual dangers.

“But wait, that’s not Halloween,” you might say. And that’s correct. It took some time to get from Samhain to the Halloween we know today.

As Christianity spread, Catholic parishes held commemorations for martyrs and saints, celebrating them during the Easter season and ultimately leading up to an All Saints’ Day. In the 8th Century, Pope Gregory III (731-741) laid the foundation for this by consecrating a chapel in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Italy, to all the martyrs on November 1 and ordering his priests to celebrate the Feast of All Saints annually. While initially confined to the diocese of Rome, Pope Gregory IV (827-844) extended the celebrations to the entire Church, ordering it to be celebrated on November 1. At this point, it’s also important to know that, in English, the traditional name for All Saints’ Day was All Hallows Day (with a hallow being a holy person or a saint), and the day before became known as All Hallows Eve, which is the linguistic source of “Halloween.” (Source: Learn Religions)

As times evolved, so did the practices surrounding All Saints’ Day. Even though the Catholic Church tried to remove the pagan roots of the celebration, communities stuck to its pagan aspects. For example, in Scotland and Ireland, people disguised in costumes went from door to door, singing songs to the dead. Another custom, the so-called “souling,” had the poor go from house to house for “soul cakes,” offering prayers for the homeowner’s dead relatives. Later on, children took up this practice, asking for gifts.

In the nineteenth century, these traditions made their entrance in the United States. Irish and Scottish immigrants—especially during and after the Great Famine—carried over guising and souling traditions. And by the early twentieth century, community parties and children’s rounds were increasingly visible in U.S. towns and cities. One theory suggests that the organized, community-based tradition of trick-or-treating is a result of curbing vandalism and physical assaults that arose by the 1920s and were exacerbated by the Great Depression.

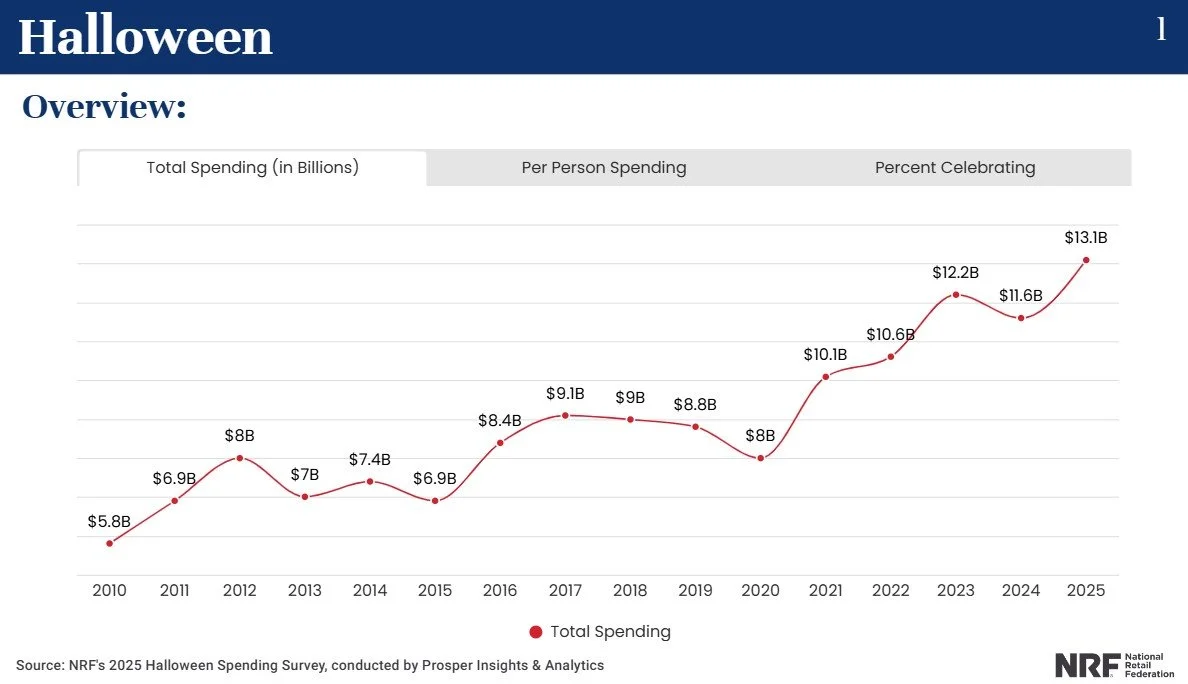

While marketing for Halloween in the U.S. started in the early 1900s, with mass-produced Halloween postcards famous between 1905 and 1915, and commercially made Halloween decorations produced by Dennison Manufacturing Company and the Beistle Company, it really took off in the 1950s, turning Halloween into what it is today, a billion-dollar business with forecasts projecting that Americans will spend about $13.1 billion on Halloween in 2025.

On a side note, it seems as if Germany had its fair share of influencing Halloween honeycomb decorations, as The Beistle Story on the company’s ‘About Us’ page shows.

Halloween in Germany: Between Church Days and Costumes

When I was a child, growing up in Germany, Halloween was an event I only knew from American Movies and TV Series. Trick-or-treating just wasn’t a thing. The closest we came to getting candies from others while going from door-to-door was during the annual Christmas tree collection—but that’s a story for another time. However, this has changed over the years, and American-style Halloween has gained traction—especially in cities and among younger people. In the 1990s, it began with Halloween-themed events, such as theme parks decorating for Halloween and offering special activities. Since then, it has constantly grown in popularity, and these days, you’ll hear “Süßes oder Saures” (“trick or treat”) and see little witches, Spidermen, and skeletons wandering the streets, while you’ll find “big” Frankensteins and adults with fake blood on their way to a costume party.

One thing that might not be so obvious to someone from outside is the tension this might bring in areas observing Reformationstag (“Reformation Day”) or silent-day regulations attached to the Catholic All Saints’ Day.

Reformation Day: From Theses to Tradition

On October 31, Protestants, especially Lutherans, commemorate Martin Luther’s challenge to indulgences (the papal practice of asking payment for the forgiveness of sins) and the start of the Protestant Reformation. On the day before All Saints’ Day, he sent his letter and the 95 Theses to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz and, as legend has it, nailed the 95 Theses on the door of the Church of All Saints, which was the Schwarzes Brett (“black board”) of the time.

What followed was a scholarly disputation that spread, with placards and pamphlets being distributed, leading to a European debate within weeks. In large part, this was due to the invention of the Gutenberg Press in 1450, which allowed commercial printing and the distribution of the 95 Theses among scholars and the common folk.

Reformationstag (“Reformation Day”) commemorations evolved over time. The centennial celebrations of 1617 prompted territory-wide services in Lutheran lands; later jubilees (1717, 1817, 1917) layered confessional identity with changing cultural politics. In 2017, the 500th anniversary, all German states made October 31 a one-time national holiday, even where it is not usually observed. As of today (2025), Reformationstag is a statutory holiday in nine federal states, with four northern states* added in permanently in 2018: Brandenburg, Bremen*, Hamburg*, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony*, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Schleswig-Holstein*, and Thuringia. Public offices, schools, banks, and most retail close accordingly, and churches hold special services centered on scripture, reform, and Christian freedom.

Allhallowtide’s Heart: Saints and Souls

I already mentioned it earlier—All Saints’ Day wasn’t always observed on November 1. Early Roman practice focused on a spring commemoration, with a key moment in consolidating a feast for “all saints/martyrs” being May 13, 609, when Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon as Basilica Sancta Maria ad Martyres. However, in the 8th Century, Pope Gregory III (731-741) laid the foundation for moving the holiday to November 1, when he dedicated an oratory in St. Peter’s “for all the saints,” aligning it with the date Celtic priests celebrated Samhain. While this date initially only applied to the diocese of Rome, Pope Gregory IV extended the celebrations to the entire (Catholic) Church.

Some modern summaries speculate that November 1 was chosen to supplant the Celtic festival Samhain, but no contemporary papal source that I’m aware of states this motive.

All Souls’ Day (November 2) emerged slightly later as a companion commemoration. It began at Cluny Abbey, where St. Odilo, abbot of Cluny (†1049), decreed an annual remembrance for all the faithful departed on November 2, kept with Masses, almsgiving, and prayers for the dead. From there, the custom spread through Benedictine houses and into the wider Western Church, with a particular focus on prayer for those in purgatory.

Together with All Hallow’s Eve on October 31, usually celebrated with a vigil, these make up Allhallowtide—a liturgical arc for sanctity and remembrance that long predates modern Halloween customs.

In Germany, Allerheiligen (“All Saints’ Day”) is a public holiday in Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, and Saarland. But it’s not “only” a public holiday in those states; it’s a stiller Feiertag (“silent day”) on which entertainment restrictions apply, but these can vary from state to state. And that’s exactly what can lead to tensions with those who celebrate Halloween in those areas, especially for young adults who celebrate until the early morning hours of November 1. In contrast, Allerseelen (“All Souls’ Day”) is not a civil holiday, but remains liturgically important and contains requiem Masses, prayers for the dead, and continued cemetery observances. From my early childhood, I remember long walks with my mother over the Catholic cemetery in my hometown during the evening hours of Allerseelen. Even though we weren’t Catholic, she visited the graves of deceased friends in their honor—and while I was too young to grasp the religious meaning of the day, I still vividly remember the flood of lit candles placed on the graves, contributing to the serene feeling of this quiet moment.

Three Days, Two Countries, Many Meanings

Late October into early November is a perennial threshold—harvest is in, daylight vanishes early, memory and mortality surface. What communities do with that time differs. In the U.S., Halloween (October 31) is largely secular and commercial—costumes, neighborhood rounds, parties—and its Christian ancestry is mostly vestigial. In Germany, October 31 is marked as Reformation Day in Protestant regions and November 1 as All Saints’ Day in Catholic regions—religious observances that can legally shape public life—while “Halloween” threads around them unevenly.

The table below gives you a condensed side-by-side comparison of the three days and their meaning in the U.S. versus Germany, their legal status, typical practices, and commercial footprint.

Layers, Not Replacements

Erntedank taught me how gratitude can be communal, simple, and church-rooted. This late-October/early November cluster shows something else: how the same dates can host very different meanings—playful boundary-crossing in the U.S.; remembrance and/or reform in Germany. Traditions rarely replace each other cleanly; more often, they layer—sometimes in harmony, sometimes in tension. That layering is real; whether it’s enriching or confusing is another question.

How is it where you live? Do you see costumes, candles, both, or neither? And what do you wish your town emphasized? I would love to see your experiences and thoughts in the comments section below!

-

Britannica – Samhain https://www.britannica.com/topic/Samhain

History – Samhain https://www.history.com/articles/samhain

Learn Religions – All Saints’ Day https://www.learnreligions.com/what-is-all-saints-day-542459

Britannica Kids - All Saints’ Day https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/All-Saints-Day/309774

History - How Trick-or-Treating Became a Halloween Tradition https://www.history.com/articles/halloween-trick-or-treating-origins

Wikipedia – Halloween - United States https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geography_of_Halloween#United_States

Wikipedia – Halloween Postcards https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halloween_card

Wikipedia - The Beistle Company https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Beistle_Company

Fast Company - The Billion Dollar History Of Trick-Or-Treating In America https://www.fastcompany.com/3020882/monsters-selling-candy-the-billion-dollar-history-of-trick-or-treating-in-america

National Retail Federation – Halloween Data Center https://nrf.com/research-insights/holiday-data-and-trends/halloween/halloween-data-center

Beistle – About Us https://www.beistle.com/about

Borders Of Adventures – Visiting Europa Park in Germany for Halloween https://www.bordersofadventure.com/europa-park-halloween/

The Morgan Library & Museum – 004. Indulgences and the Ninety-Five Theses https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/online/word-and-image/3

Reverend Luther – The Ninety-Five Theses http://reverendluther.org/pdfs/The_Ninety-Five_Theses.pdf

Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland – Die 95 Thesen (German) https://www.ekd.de/95-Thesen-10864.htm

Wikisource - Works of Martin Luther https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Works_of_Martin_Luther%2C_with_introductions_and_notes/Volume_1/Disputation_on_Indulgences

History – Printing Press https://www.history.com/articles/printing-press

Britannica – Protestantism https://www.britannica.com/topic/Protestantism

Schleswig-Holsteinischer Landtag – Reformation Day becomes a holiday (German) https://www.landtag.ltsh.de/nachrichten/18_02_feiertag/

Deutsche Welle – Martin Luther's daring revolution https://www.dw.com/en/martin-luthers-daring-revolution-the-reformation-500-years-on/a-41084136

Britannica – Saint Boniface IV https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Boniface-IV

Wikipedia – Pantheon, Rome https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pantheon,_Rome

Britannica – All Souls’ Day https://www.britannica.com/topic/All-Souls-Day-Christianity

Catholic Online – All Souls - The Western Celebration https://www.catholic.org/saints/allsouls/#:~:text=Historically%2C%20the%20Western%20tradition%20identifies,only%20in%20the%20fourteenth%20century

Erzbistum Köln – Holiday All Saints’ Day – Origins and Traditions on November 1. (German) https://www.erzbistum-koeln.de/presse_und_medien/magazin/Feiertag-Allerheiligen-Ursprung-und-Braeuche-am-1.-November/